Reading Time: 2 minutes

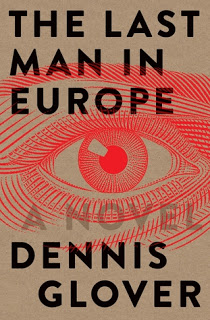

If, like me, you were both fascinated and terrified by George Orwell’s unforgettable classics ‘Animal Farm’ and ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’, then Dennis Glover’s first novel, ‘The Last Man In Europe’ (2017) is likely to appeal.

This is not a biography of Eric Arthur Blair, better known to us by his pen-name George Orwell, but it does closely examine Orwell’s personal, literary and political life during and immediately after World War 2, the period during which he wrote ‘Animal Farm’ and ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’.

Glover notes that his book ‘is a work of fiction, but one that attempts to keep as close to the historical facts as it is possible without sacrificing the dramatic requirements of the novel form’. The result is a book that entertains like a novel and informs like a documentary.

What initially attracted me to this book was Glover’s elegant writing style. Robert Manne has observed that the book is ‘written uncannily in the style Orwell would have used if he had decided to write a novel about his own life.’

‘The last man in Europe’ takes us into Orwell’s unorthodox and somewhat sad personal life, and his struggles to make ends meet as a writer, reviewer, journalist, and literary critic. In these roles Orwell crossed paths and developed personal relationships with other prominent English literary figures of the time, and Glover succeeds in presenting these mythical greats as fascinating dinner companions and verbal sparring partners.

I was particularly fascinated by the impact political events such as: pre World War 2 English politics, Spanish Civil War, Post-revolution Soviet Union, Stalinism, and the early Cold War, on the evolution of Orwell’s political views and hence his writing. Glover is careful to explain that the dystopian world of ‘1984’ is neither ‘an imaginative work of science fiction’ nor an attack on fascism and communism. He presents the motivation for these monumental books as a reflection of Orwell’s belief in democratic-socialism and his strident opposition to authoritarianism. Glover sees the nightmare future presented by Orwell as ‘an amplification of dangerous political and intellectual trends he witnessed in his own time.’

Glover tackles the controversial ending of ‘1984’ in which Winston’s opposition appears to be finally defeated when he accepts that 2+2=5. Orwell’s realisation that the original ending was too bleak and suggestive of the triumph of authoritarianism through defeat of ‘thoughtcrime’ led to the deletion of the 5 in ‘the second impression of the first edition’ – something that Glover suggests injected ‘subtle strain of optimism…consistent with Orwell’s belief…that totalitarian governments would eventually be destroyed in the name of freedom’.

Glover’s background as a newspaper columnists, academic with a PhD in history, and a ‘a speechwriter for Labor leaders’ adds credibility to the often weighty subject matter of this book. Perhaps most astonishingly, Glover shows that it is possible for an academic to engage and not bore the reader when informing and providing much food for thought – on matters particularly significant at a time when the world veers away from democracy toward authoritarian rule.

(Visited 48 times, 1 visits today)