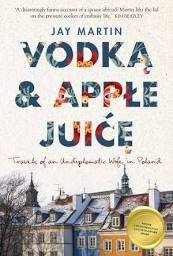

Reading Time: 4 minutes‘Vodka & Apple Juice: Travels of an Undiplomatic Wife in Poland’ – Jay Martin

Jay and Tom were a young successful young professional couple working in Canberra when Tom was offered a posting to the Australian embassy in Warsaw. On moving to Poland, Jay found herself in the unfamiliar role of ‘the wife’ – a diplomatic wife. This book is her account of the three years she and Tom spent in Poland. In her ‘Author’s Note’ Jay describes the book as being factual as far as political events and individuals are concerned but fictional in that non political characters and other events depicted are conglomerates of actual persons and events. As far as her descriptions and commentary on Poland itself, Jay writes that ‘Of all the characters I wrote about, [Poland] was the one I most wanted to do the most Justice to.’

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book, largely because it is so well written, full of good natured humour and thickly sprinkled with valuable insights. It is written by someone with an open mind, and who is intelligent yet not arrogant nor judgmental. Apparently my liking for this book showed, as on a number of occasions, when reading the book, I was told that I appeared to be finding this book particularly enjoyable.

Jay writes that while Tom spends most of the three years engaged in never ending diplomatic work, which she colourfully describes from her perspective as the ‘diplomatic wife’, she was also hired to help out at the understaffed embassy. Jay describes her determination not to confine herself to just being a diplomats wife, or to minimise her interactions with Poland, as many more experienced diplomat wives were.

Her behind the scenes account of embassy life is a practical account of both the day to day as well as the exotic. It is an account that presents the glamour of diplomatic postings as only one facet of diplomacy that is often overwhelmed by the more mundane. Visits by Australian signatories such as Senator Penny Wong and Prof Gareth Evans are described in a manner that offers some interesting insight into those personalities. Jay also sympathetically immerses the reader in the tragedy that befell Poland when a large number of the country’s most prominent leaders and citizens died in a plane crash in Russia. When a volcanic ash cloud prevented Governor-General Quentin Bryce and other heads of state and political leaders from attending the victims’ funeral, Jay reveals the resulting frantic diplomatic manoeuvrings.

To extend her life beyond the chores of a housewife and the endless embassy functions she is expected to attend, Jay travels extensively within Poland and occasionally to other European locations. Her accounts of her travels prove to be much more helpful and insightful than reading a commercial guidebook. As Jay illustrates, guidebooks for a country such as Poland can be misleading or outdated. Her comparisons and contrasts with neighbouring countries such as Ukraine, Germany and Russia prove to be illuminating attempts to better understand Poles and Poland. These accounts of her observations provide valuable information on which to decide whether to visit a country that was decidedly drab under communist rule for for about a decade after.

Jay’s determination to speak Polish, to see Poland, and to volunteer as a researcher for a Polish project on the 1944 Warsaw Uprising is as enriching for the reader as it was for Jay. Her observations about Polish society and history are particularly valuable in that they present Poland and Poles from their own perspectives, but filtered or translated by Jay. In her comments on current Polish society Jay does not skim over behaviour and customs that she finds quaint but rather than just ridicule she seeks to make sense of them via the context of the nation’s psyche and history. In a number of passages. Jay also dwells on the sense of belonging and identity associated with nationality and citizenship, concepts which are particularly significant in the context of Poland’s ever changing borders and fight for sovereignty.

This book also has much to offer those of us with an interest in linguistics. Unlike Tom, Jay studied Polish in Canberra prior to leaving for Poland. She continues to learn and improve her Polish and in so doing illustrates in endless and invariably entertaining stories why interpreting or translating is never simply about finding the equivalent words.

The aspect of the book’s storyline that didn’t particularly resonate with me was that in which Jay dealt with her relationship with Tom and her thoughts on whether or not her marriage would survive the Warsaw posting. I simply found her brief, occasional and abruptly changing views on what must have been an ever present and consuming issue to be unconvincing and virtually impossible to relate to. Perhaps it’s simply that Jay is not a romance writer. But it may be that other readers will disagree with me and find this aspect of the book to be compelling.

It’s true that this is a book of precise clear expression. It may well be that in this respect it reflects Jay’s experience in policy and report writing where clarity, simplicity and brevity are valued rather than the more indulgent mood setting and painting of pictures with words, and other tools employed by authors of fiction novels and by other story tellers. While the absence of such writing techniques does not appear to detract from Jay’s accounts of her life in Warsaw, it may account for what struck me as an inadequate or unconvincing treatment of emotions and the ups and downs of her marriage.

Before you pick up this book, be warned that unless your Polish is fluent, you may feel the need to frequently consult a Polish-English dictionary, as the author regularly injects Polish words or phrases without translation. Perhaps this is designed to engage the reader in Jay’s quest to master the language.

Nit picking aside, this is a thoroughly enjoyable read that I wholeheartedly recommend.

(Visited 48 times, 1 visits today)