A Husband’s Right to Sex with His Wife – A ‘Fundamental Human Right’

It would appear that while some heterosexual men see their wives as autonomous individuals, others cling to legal rights previously enjoyed by husbands in traditional marriages.

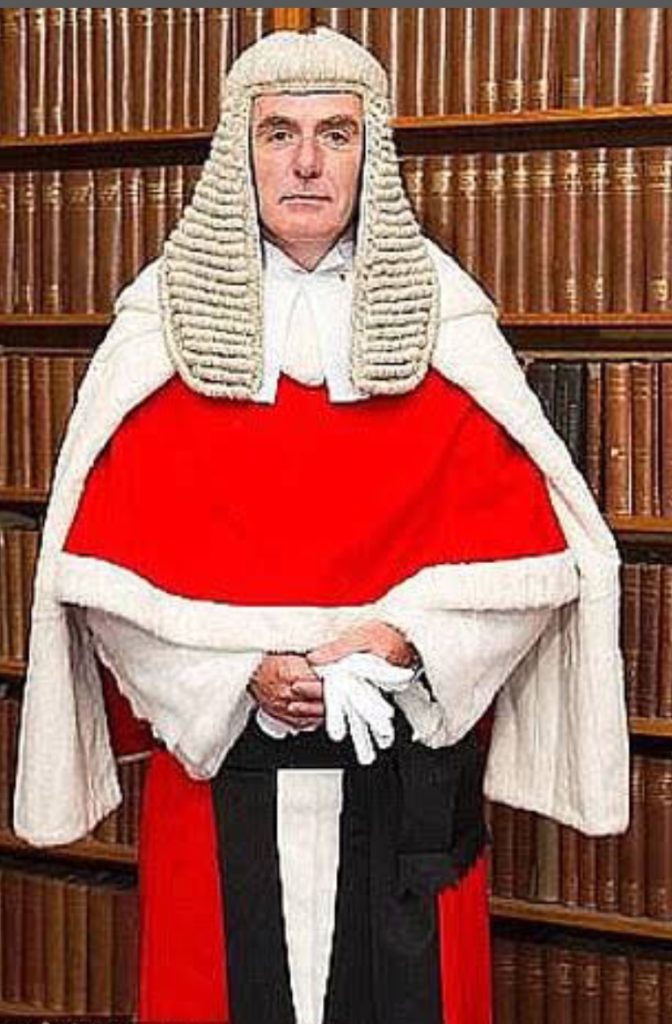

English judge, Justice Anthony Hayden appears to fall into the latter category.

Facts

A marked decline in a woman’s cognition led her support workers to ask an English court to make an order. They wanted the Court to prevent the woman’s husband of over 20 years, from having sex with her. The reason for their application was that as they believe that she now lacks the capacity to consent to sex.

At the preliminary hearing in the Court of Protection, Justice Anthony Hayden, expressed his concern for how such an order would affect what he saw as the rights of the husband. He stated, ‘I cannot think of any more obviously fundamental human right than the right of a man to have sex with his wife – and the right of the state to monitor that,” he said. “I think he is entitled to have it properly argued.’

Commentary

The concept of a “fundamental human right” of a man to have sex with his wife, referred to by the judge, has quite a history. This is precisely the view that helped ensure that until the early 1990s Australian men could not be charged with raping their wives, even after the couple had separated. It also accounted for husbands being able to sue those who took or assisted their wives to leave them, for for the loss of their wive’s sexual and other domestic services.

A husband’s right to sex with his wife stemmed from what was perceived to be the nature of a marriage contract. In consenting to marry, a woman was deemed to consent to sex for the duration of her marriage (irrespective of her actual consent or lack thereof, at any time).

Despite significant changes in societal views and laws governing marriage and sex, those who appear not to have adjusted (including Justice Hayden, it would seem) express views reflective of a bygone era.

That Justice Hayden sits on The Court of Protection is in itself troubling, as it is that Court’s role to protect the rights of those thought to no longer possess the capacity to make their own decisions. Consequently, a more appropriate concern for Justice Hayden to voice may have been the wife’s rights to have or not to have sex. Instead he seemed to echo the caricatured view of a wife’s sexual experience as one of ‘lying back and thinking of England’.

The judge appeared to suggest, that a man’s right to have sex with his wife (who is presumed to consent by virtue of being his wife) continues for as long as she is capable of understanding and being able to consent to what he proposes to do to/with her.

I am concerned by reports suggesting that the woman’s capacity to consent is to be the extent of the enquiry. Such an assessment would impliedly equate a wife’s capacity to consent with her actual consent. There Are countless reasons why she would not consent to sex with her husband on some, or all occasions. She may also not consent after being made aware that (perhaps contrary to her understanding) it is not her husband’s right to have sex with her, and that agreeing to have sex with him is not her obligation as a wife.

The ‘learned’ judge in this case appears to reveal too much about his own understanding of marital sex and contemporary marriage. Where the parties to a marriage have equal rights and responsibilities (as they legally do, today), neither can possibly be held to have a right to sex with the other, as both parties are required to consent.

The judge’s views on ‘the right of a man to have sex with his wife’ have, not surprisingly, been roundly criticised. One Labour MP suggested that the statement ‘legitimizes misogyny and woman-hatred’, and observed that, ‘No man in the UK has such a legal right to insist on sex. No consent=rape.’

The Australian Situation

The role of the English Court of Protection is to determine a person’s capacity to make decisions for themselves, and in the absence of such capacity to appoint someone to make decisions on their behalf.

In Australia, this role is performed by Tribunals such as SAT(WA), VCAT (Vic), or QCAT (Qld). While Australian law also requires both parties to consent to sex, elderly demented couples, who clearly lack capacity to consent, are permitted to cohabit (if it is able to be determined that they want to and their carers consider it to be in their best interests), I am not aware of any Australian cases that are similar to the English case.

While many intellectually disabled and mentally ill people are incapable of consenting to sex, the law only tends to interfere in their sexual lives where they are considered to be At risk of being exploited by others, or of acting in a manner that would place them in danger.

The Real Issue

In my view, the real issue in the English case is not whether the husband should be prevented from having sex with his wife, but whether the wife is capable of consenting, and if she is not capable, whether her incapacity to consent calls for some informal or formal means of ensuring that HER wishes as to sex are addressed in a manner that is in HER best interest. The husband’s wishes are irrelevant as long as the wife does not consent, is incapable of consenting, and it is clearly determined that she would not consent if she were able to do so, or that having sex with him it is not in her best interests.

This case highlights how far we have to go before society recognises the equal rights of women. And, in particular that women are autonomous sexual beings, that a wife’s role in marriage is not one of looking after her husband’s needs including his sexual needs – irrespective of her wishes. whether she consents to sex, and if incapable of consenting whether it is possible to determine whether if she was capable, she would consent

Writing in semi retirement, my blogs reflect the scope and focus of past careers in education, law and academia, and my ongoing sessional work as a Tribunal Member . My occasional blogging also permits me to voice my opinions on social issues and to share some of my eclectic personal interests. (See the right sidebar for fuller profile).