Ian McEwan’s ‘Machines Like Me’

Ian McEwan is adamant that his latest novel ‘Machines like me’ is not science-fiction. Strictly speaking it is. Yet, it isn’t, because its historical what-if fiction is not the book’s primary focus, but rather one that facilitates, elaborates and freshens the book’s contemporary themes, through its comparative nature and novelty.

Ian McEwan is adamant that his latest novel ‘Machines like me’ is not science-fiction. Strictly speaking it is. Yet, it isn’t, because its historical what-if fiction is not the book’s primary focus, but rather one that facilitates, elaborates and freshens the book’s contemporary themes, through its comparative nature and novelty.

McEwan’s early 1980s London is significantly different to the one baby-boomers remember, or that younger generations may study as history. The difference that is central to this book’s story is the parallel world’s advanced information technology, in many ways similar to contemporary levels of development, but with one major distinction.

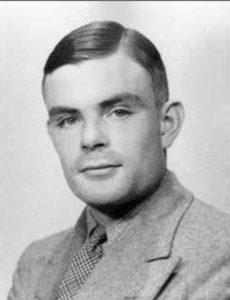

Alan Turing

Alan Turing, who deciphered the Enigma Code, was not hounded to death for his homosexuality, as depicted in the brilliant film,‘The Imitation Game’. In McEwan’s alternative world, Turing lives on to lead the world in a collaborative developments and breakthroughs in the field of Artificial Intelligence. Turing also plays a cameo role in this book.

Our narrator and central character is Charlie, an intelligent young man, struggling to come to grips with his early failures, who makes a meagre living by playing the stock market online. He uses an inheritance to purchase Adam, one of a small batch of experimental lifelike and thinking human robots.

At around the same time Charlie successfully makes a long overdue move on Miranda, the attractive bookish doctoral candidate who lives in the apartment above his. They jointly program Adam’s personality.

The interaction between their imperfect humanity and the logical and feeling Adam provide McEwan with a range of issues to explore and analyse. Here the author impresses with his vast acquired knowledge and enviable skill in conveying it to the reader.

The backdrop to the exploration of personal relationships, complicated by an artificial intelligence entity capable of not only the emotion bust also the act of love is our characters’ response to the global events of this parallel reality.

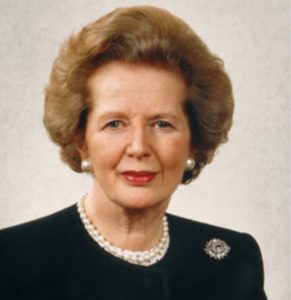

Argentina’s President Galtieri

Argentina’s acquisition of advanced military weapons accounts for Britain’s humiliating defeat in the Falklands war.

Consequently, Maggie Thatcher is voted out of office and is unable to undertake the reforms for which we either love or hate her.

PM Maggie Thatcher

In other interesting reforms the Beatles reform and record new music and Billy Carter defeats Ronald Reagan and serves a second term. I was not surprised to read that Tim Garton Ash, one of the most authoritative historians on the 1980s had been consulted on an earlier draft.

One of McEwans most notable strengths is his ability to write about human feelings and emotions in a manner that is realistic, raw and incisive without resort to cliche’s and predictable storyline’s. In this respect he excels in this unique context of a three way relationship that includes an artificial human. A factor that further complicates this unclear equation is a young boy being rescued from a dysfunctional and abusive home.

Through his treatment of Miranda’s secret legal history, McEwan invites the reader to make his or her own judgment on competing ethical and moral questions. The solutions offered are a welcome change from the pragmatic self serving ones that alarmingly tend to be passed off as life-like.

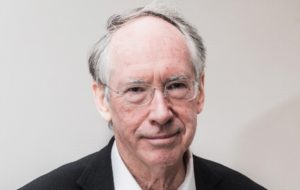

Ian McEwan

McEwan’s earlier books, such as ‘Atonement’, may have been somewhat challenging to read. This book on the other hand is a delightfully easy and quick read, yet offers much to savour.