The Mandate Furphy

The Morrison Government’s Claimed Mandate

The Australian government claims it has a mandate to implement specific promises it made during the election campaign leading to its election. We have heard governments say this for as long as we can remember. Yet if we pause to consider this claim, it soon becomes clear that it just does not add up.

During an election campaign, individual candidates and political party leaders outline their policies and make promises as to what they or their party will do if elected. One such promise made by the liberal-national party coalition at the last federal election related to tax reform.

That the Coalition parties were re-elected to government means their candidates won a majority of the House of Representatives seats. Yet, the government does not have a majority in the Senate.

That the Coalition parties were re-elected to government means their candidates won a majority of the House of Representatives seats. Yet, the government does not have a majority in the Senate.

This means that to pass legislation the will need the support of the opposition or at least the smaller parties or independent Senators.

Nevertheless the government, and in particular the Prime Minister, claim that, having been elected to government, they have a mandate to embark on the foreshadowed tax reform because they ‘put this proposal to the people’.

Questions Arising

This assertion poses a number of questions relating to how we decide whether the government has a mandate to put into practice what it promised to do if elected. Is being elected to govern a sufficient mandate to implement a specific election promise? Do non government have a mandate to oppose the government’s promised reform, or should the mandate claimed by the Government be honoured by non government politicians? Does the election of a government promising certain action grant a mandate for that action to be undertaken even if the government lacks the numbers to pass required legislation?

What is a Mandate?

To have a mandate means to be authorised, commissioned or empowered. With reference to a pre election promise a mandate amounts to an endorsement of a political proposal to act on a policy or enact legislation.

The is the Mandate of an Election win

At parliamentary elections we cast a vote for a candidate. In doing so, we are likely to also be casting a vote for a political party. If voting for a major party candidate, we are probably hope that the party will have a sufficient number of candidates elected to enable its leader to be commissioned to form government.

In this sense an election win may be a mandate to govern.

Is an election Win a Mandate for Specific Promises and Legislation?

Unless a candidate is running on one issue only, no one can know for sure why electors voted for the candidate. Consequently, it is simply not possible to determine whether electors’ votes for a candidate or party were an endorsement or authorisation of government action.

A party may say, ‘A vote for us is a vote for tax reforms’, but electors may have other reasons for voting for that party. For instance, as voting is compulsory voters may not be able to bring themselves to vote for any of the other candidate. Alternatively, they may vote for the party because they are attracted to one or more of its other policies. They may even vote for the party in spite of its policy on tax reform.

On that basis it is safe to say that a vote in an election is not necessarily vote for a specific policy, issue or program. Instead it is more likely to be a vote for a candidate, party, party leader and/or the party’s their overall policy platform

Can a Government Gain a Clear Mandate for Specific Action?

Our political system is not a direct democracy. The elected representatives who make our laws and form government are not required to, and generally don’t consult the people before enacting laws or new policies.

Amending the Constitution

The only time that parliament requires the approval of the people is when it proposes to amend the Constitution. A referendum must be held and the approval of a majority of voters in a majority of states and a majority overall must be secured. Only 8 out of 42 such proposals have been approved in the 118 years since federation.

Non-Binding Opinion on Non-Constitutional Issues

However, at times Australia’s federal government has sought non binding advice or opinion of the Australian people on specific initiatives.

It is in this way that a clear mandate for government action on a particular issue can be secured through a plebiscite, or less clearly from a public survey.

Plebiscites

Parliament is required to pass enabling legislation facilitating the holding of a Plebiscite. A plebiscite entails compulsory voting by all eligible electors. It is conducted by the Electoral Commission.

Parliament is required to pass enabling legislation facilitating the holding of a Plebiscite. A plebiscite entails compulsory voting by all eligible electors. It is conducted by the Electoral Commission.

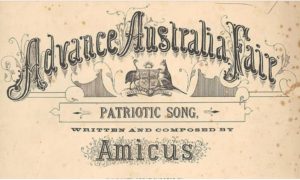

Plebiscites have been held on the issue of military conscription during world war, in 1916 and 1917. The Fraser government also held a 1977 plebiscite on the national song to be played other than on regal or vice regal occasions.

Surveys

A plebiscite was not held on same sex marriage as parliament failed to pass the enabling legislation — Plebiscite (same-Sex Marriage) Bill 2016. Instead the government held The Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey 2017 which the government was authorised to do by the Statistics Act 1905.

The conduct of a survey was not unprecedented. The Whitlam government had held an opinion survey on the national song in 1974.

The conduct of a survey was not unprecedented. The Whitlam government had held an opinion survey on the national song in 1974.

However, the postal survey of 2017 was criticised by many including Michael Kirby.

It was criticised because it was not held with the agreement and clearly defined purpose and parameters determined by parliament. Voting was not compulsory, and hence arguably not representative of the views of the population. It was conducted over a significant period of time, and therefore was not a snap shot of public opinion. The secrecy and security of the votes be guaranteed as it was conducted by post. And, it wasn’t conducted by the electoral commission, but by the Australian Bureau of statistic.

Nevertheless it was accepted that even the postal survey provided a clear indication of the views of Australian and gave a mandate for the legislation to be enacted

The use of plebiscites and surveys by earlier Australian governments reveals how public mandates for specific proposals can be secured.

In addition, there are other reasons for why election to government does not in itself signal a mandate to pass laws inspite of adequate parliamentary numbers required to do so.

Other Parliamentarians also have mandates

It is not only governments that are given a mandate. Each elected candidate or party whose policies are at odds with that of the government has a general mandate to act as they or their party indicated they would. They are empowered to represent their electorates and electors who preferred their policies to those of the elected government. There is no reason why they should not opposing government proposals in line with their policies.

To suggest that the government has been given a mandate to enact legislation even where the government lacks the support of the required numbers in parliament ignores the mandate of those elected to represent contrary views. It also ignores our constitutional separation of powers between the executive (government) and the legislature (parliament).

Where a government feels that their election mandates the enactment of a law, they should introduce proposed legislation and persuade parliament to pass it. Whether it passes is up to parliament and the equally unclear specific mandate of opposition members to oppose such legislative proposals.

The Opposition’s Mandate

However, what is clear is that the opposition members have their own general mandate to represent their constituents and to pursue their or their parties’ policies. In particular the minor parties in the Senate may be elected with a the mandate to ‘keep the bastards honest’, as the the now defunct Democrats were.

Many of us vote for the Greens on the Senate ballot paper specifically to put a brake on populist or otherwise unwise legislation. Clearly, a government’s claimed mandate should not trump the corresponding mandate to put a break on such an initiative.

The non-government members’ clear general mandate to oppose, or at least subject the proposal to close scrutiny and possible amendments, must be contrast with the government’s fictional mandate to pass their proposed law irrespective of the views of opposition parliamentarians.

Conclusion

A government seeking to pass legislation legislation needs to secure majority support in both houses of parliament. The election of a government through a majority in the lower house does not endorse the passing of any legislation, if the government parties do not also command a majority in the Senate.

On that basis alone the government cannot be said to have been given a mandate to pass a law if the electorate has not seen fit to elect a majority in both houses. The electorate’s message in electing a non government majority in the Senate could arguably suggest that any proposed legislation is to be subject to scrutiny, review, amendment or rejection by the Senate.

The claim of a mandate to implement a policy or enact legislation put to the people prior to an election is simply unfounded bluff, spin or wishful thinking.