Pell’s Appeal – The Final Steps

Pell’s Appeal – The Final Steps

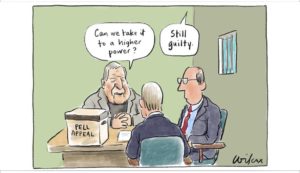

George Pell has one remaining avenue of appeal – the High Court. In this post, I briefly outline what is involved in pursuing such an appeal.

The Remaining Appeal Option

The High Court is Australia’s final court of appeal. Unlike the US Supreme Court, our High Court hears appeals on both federal and state law. However, there is no right to appeal to the High Court in a state law criminal matter such as George Pell’s.

The High Court would simply not cope with the workload if obliged to hear all appeals from lower courts. That the High Court’s workload needed to be reduced was recognised in the 1970s. Consequently, some of the Court’s jurisdiction was moved to the newly created Federal Court. The Court also divested itself of its exclusive powers to hear certain categories of cases that were able to be brought directly to the Court. In this way, by 1984 ‘as of right’ appeals to the High Court were virtually eliminated. The few categories of cases exempt from this requirement are not relevant to George Pell’s case.

So, what is involved in securing special leave?

The High Court determines which appeals it will consider through a process of special leave applications. Such applications involve written submissions and brief oral presentations. Where an Applicant is unrepresented the Court is unlikely to hold an oral hearing.

Applicants bear the onus of proof, although in some cases the Court may ask Respondents why the leave sought, should not be granted.

The current practice, in an appeal such as Pell’s, is for two Justices of the High Court to consider the written applications and then invite the appellants to orally present their case and or answer questions put to them by the judges. Both sides have twenty minutes each to present their case. The applicant has an additional five minutes in reply.

What determines Whether Granted Leave?

The criteria by which the Justices determine which appeals will be heard are:

1. That the proposed appeal is of legal significance to the Australian public, and/or

2. That the decision sought is so erroneous that the very interests of the administration of justice require the appeal to be hear.

In addition, it should be noted that over the past two decades the High Court has encouraged appeal courts in Australian state and specialist jurisdictions to act as final courts of appeal, unless the issues of law raised on appeal have broader national significance.

George Pell’s team is unlikely to meet the criteria of being allowed to appeal to the High Court.

Why Pell is Unlikely to be Granted Special Leave

That George Pell and his lawyers and supporters don’t like or disagree with the decision of the Victorian Court of Appeal is no ground for special leave

The First Appeal

It is difficult to see that the decision of the Court of Appeal raises a question of law requiring clarification or correction by the High Court

It was not the role of the three Justices of the Court of Appeal to second guess the jury and determine whether Pell was guilty. But they did have to rule on the main ground of appeal – that in view of the evidence presented at the trial, it was unreasonable for the jury to find Pell guilty.

Pell’s legal team put forward 13 reasons why on the evidence the jury should have had sufficient doubt as to his guilt, to find Pell not guilty.

The Minority

In his dissenting judgment, Justice Mark Weinberg found that the evidence precluded the jury from finding Pell guilty. He held that the evidence cast significant doubt as to Pell’s guilt. Perhaps, not surprisingly, Weinberg now finds himself hailed by right-wing commentators. He is even portrayed as the sole protector of the public’s faith in the judicial system.

The Majority

The other two judges on the panel were more senior, but less experienced in criminal law. They were Chief Justice Anne Ferguson and the President of the Court of Appeal, Justice Chris Maxwell. They found that the evidence still left it open to the jury to find Pell guilty. They held that the 13 reasons submitted for the Appellant fell well short of the conclusion suggested.

The evidence in question related largely to the Cardinal’s clothing and a crowded Cathedral. Both allegedly precluded him from doing what was alleged.

Is anyone seriously suggesting that the High Court would overturn this finding of the majority? To do so, the High Court would be asked to say that the evidence was such that a finding of guilt was unreasonable. Yet the High Court would also be aware that the two most senior judges in Victoria, who saw and heard the same evidence as the jury, found that evidence questioning guilt fell well short of requiring the jurors to have a reasonable doubt as to Pell’s guilt.

This split decision smacks more of the application of law rather than its interpretation. The decision of the Court of Appeal was reported as a finding of guilt. It wasn’t. It was a decision on whether the evidence left the jury with the option of finding Pell guilty.

An Appeal to the High Court Is Not Just One More Appeal

A High Court appeal would not resemble a retrial. Nor would it replicate the Court of Appeal’s reexamination of all the evidence. A High Court appeal would be an examination and ruling on a question of law. Even then, the question of law would need to be such as required intervention by the nation’s highest court.

Which leaves me inclined to suggest that George Pell’s attempts to clear his name have run their course.

Anne Wilcox, Sydney Morning Herald, 8/8/2019

In which case …

Writing in semi retirement, my blogs reflect the scope and focus of past careers in education, law and academia, and my ongoing sessional work as a Tribunal Member . My occasional blogging also permits me to voice my opinions on social issues and to share some of my eclectic personal interests. (See the right sidebar for fuller profile).