‘David Attenborough: A Life On Our Planet’ – Reviewed

I rarely watch nature films. However, the prospect of watching Sir David Attenborough’s latest, and perhaps last, film on the large screen seemed far removed from watching a lion tear apart some slower and weaker animal, or smiling at the playfulness of baby animals.

Since the mid-1950s Attenborough has sought to not only make us more familiar with nature, but also aware of threats to the vulnerable balance of our natural world – a world in which we humans are only one species.

Since the mid-1950s Attenborough has sought to not only make us more familiar with nature, but also aware of threats to the vulnerable balance of our natural world – a world in which we humans are only one species.

This film sums up Attenborough’s life’s work, focusing on the significance of how his life and the habitat on earth have changed during his lifetime. This link between segments of his life and corresponding changes in nature turned out to be an impressive way of making us appreciate our link with, and impact on nature. Attenborough’s long life and consequent seven decades of observing nature permit comparative presentations graphically illustrating the human impact on and destruction of nature.

Having turned 94 since the film was made, Sir David calls this film, ‘my witness statement and vision for the future. The film also succeeds in demonstrating how humankind’s expansion and exploitation of nature are altering the fine balance of life on earth. Attenborough offers a timeline of predictions for this century if humankind does not take the steps required to reverse the current destruction of nature.

Distinguishing itself from other presentations on the likely impact of humans on our planet, in this film, Attenborough outlines specific steps that need to be taken by governments and individuals to undo the damage done. The steps he outlines seem surprisingly doable, and as our group agreed in our post-screening discussion, the steps do not require us to abandon the western trappings of our lives. What, David Attenborough suggests instead, amounts to humans recognising the balance in nature that needs to be re-established, and how humans can coexist rather than wage war on nature.

The city of Chornobyl was abandoned in 1986 and is currently in the process of being reclaimed by nature. It provides the bookends of this film and a confronting visualisation of nature reclaiming what a human ‘mistake’ had destroyed. Other human assaults on nature, such as deforestation, Attenborough suggested are also mistakes. He asks us to view other human acts causing dire consequences as mistakes that are calling for changes to be made so that we can restore this planet’s natural balance.

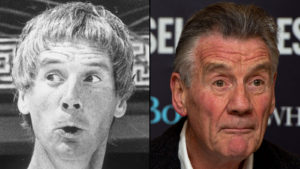

The film was followed by a recorded interview of David Attenborough by Michal Palin, a former member of the Monty Python team, and long-time traveller and documentary maker. In this interview, Michael Palin is our surrogate – asking questions and seeking further information about the film. The interview is also a lighthearted chat about Sir David’s life on the road and dealing with fame. This segment, in particular, presents Attenborough as someone with whom we can identify – making the changes in our natural world during his life, so much more personal.

The film was followed by a recorded interview of David Attenborough by Michal Palin, a former member of the Monty Python team, and long-time traveller and documentary maker. In this interview, Michael Palin is our surrogate – asking questions and seeking further information about the film. The interview is also a lighthearted chat about Sir David’s life on the road and dealing with fame. This segment, in particular, presents Attenborough as someone with whom we can identify – making the changes in our natural world during his life, so much more personal.

The film is currently screening in cinemas but is expected to be available on Netflix for viewing at home. I would recommend seeing this film in the cinema as the as amazing nature footage we have come to expect from Attenborough is breathtaking on the large screen, and because of the post-film Michal Palin interview, which provides additional fodder for later reflection and discussion will not be available on Netflix.

The film is currently screening in cinemas but is expected to be available on Netflix for viewing at home. I would recommend seeing this film in the cinema as the as amazing nature footage we have come to expect from Attenborough is breathtaking on the large screen, and because of the post-film Michal Palin interview, which provides additional fodder for later reflection and discussion will not be available on Netflix.