Reading Time: 9 minutesThe longer I reflect on Paweł Pawliknowski’s film, Cold War, the more convinced I become that it is a cinematic masterpiece.

The film’s subject matter is a fifteen-year love story. It is largely set in Poland between 1949 and 1964

This period coincided with the first half of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and other communist countries such as Poland, and the United States and its Western Allies.

Cold War is filmed in black and white – as was Iris, the Director’s 2016 Oscar winning film. It quickly becomes apparent that the black and white images are totally in keeping with the mood, settings, and depicted era. The monochrome further enhances the stylish composition of the film’s portrait/poster quality and facial study images. Consequently, it would be a travesty to even contemplate this film in colour.

The film opens with Wiktor, a composer and musical academic touring Poland. Wiktor’s character is presented by Tomasz Kot, a popular Polish actor with some 34 films to his credit. Wiktor is recording traditional Polish folk music, and auditioning singers and dancers for a national song and dance troupe.

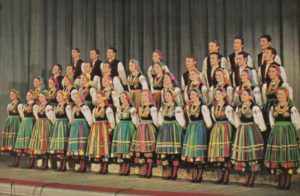

Polish Cold-War Era Song & Dance Troupe

Those selected are to tour post-war Poland promoting national pride and identity through the performance of Polish traditional songs and dances – and most notably those of the Górale (Polish Highlanders). The depicted troupe appears to be based on ‘Mazowsze’ the folkloric song and dance troupe that every Pole recollects.

Wiktor is fascinated by Zula, a talented, beautiful, ambitious through unsophisticated young woman. Zulu, who reciprocates Wiktor’s interest, is played by Joanna Kulig, a pianist, vocalist and award winning star of Polish television and film.

The Political Context

Some appreciation of Poland’s social and political context of the period – with which only older Poles are likely to be intimately familiar – may shed some light on both the progression of Zulu and Wiktor’s love story, and the significant period of political history, in which it is set.

At the conclusion of World War 2, Poland barely resembled the nation it had been before the war – only six years earlier.

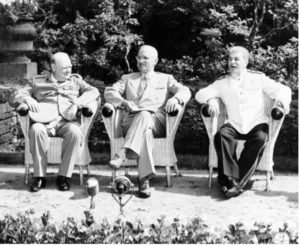

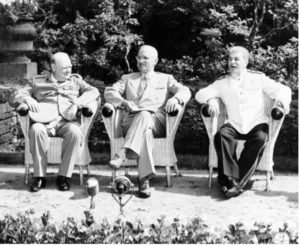

The Potsdam Conference

It had shrunk in size by about a sixth, and its borders moved west.

The new borders sere approved by the US, UK and the Soviet Union at the Potsdam Conference.

This agreement gave much of western Poland, including a number of cities and much valuable agricultural land, to the Soviet Union. In return, eastern and northern Poland expanded incorporating smaller pieces of Germany.

Of particular significance to this film, Poland’s population fell by one third, or some 11 million, and the composition of Polish society became homogeneously Polish. Hitherto and historically, Poland had been a commonwealth of Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Germans and other smaller ethnic groups.

A number of factors account for these significant changes.

One in six Polish citizens died during the war. This included most (over three million) Polish Jews, and at least 2 million ethnic Poles.

Shortly after the end of the war, a significant number of surviving Poles of Jewish ethnicity emigrated to the west or to the newly created state of Israel.

By 1949 eight million, of Poland’s ten million pre-war citizens of German ethnicity, are also said to have fled or been expelled from Poland.

Millions of other Polish inhabitants were relocated from Poland to Germany, Ukraine and Russia, while Millions of Poles living in what used to be west Poland were relocated to populate the eastern areas annexed from Germany.

In addition, at least 200,000 Poles are said to have been imprisoned, killed or deported to the Soviet Union by the occupying Soviet forces and their Polish allies.

Consequently, the country had to rebuild, find a new national identity and leadership, and do so in a manner acceptable to the Soviet Union.

Poland’s military and political leaders, and the nation’s intellectual, arts and business elites had been systematically exterminated, first by the Nazis, then by the Soviets, and, in the first years covered by the film, by the fledgling Polish communist leaders, seeking to impose an alien ideology on the population, and determined to eliminate any potential opposition.

The communists were able to assume and hang onto power for a number of reasons. Because of the ever present threat of Soviet invasion. As any potential opposition had been eliminated. Due to the west’s unwillingness to intervene. And, because the war-weary population chose to cooperate rather than fight the communists, and even warmed to having their basic needs met in a socialist state.

Many of the communist government’s policies were applauded by Poles. Even though the Soviet Union pressured Poland into rejecting Marshall Plan aid, by 1948 industrial output had returned to pre war levels and Poland’s standard of living was rising rapidly. Public opposition to the new rulers came to be largely confined to resentment of the privileges the governing communist party bestowed on its members.

The Yalta Conference had appeared to guarantee the setting up of a broad representative Polish government pending the holding of free democratic elections. However, the Soviet Union ensured that the Polish government in exile was excluded, that other opposition was eradicated, imprisonment or forced into exile, and that elections were rigged or won through intimidation. In this way, by 1949, Poland became a one-party communist state, a satellite of the Soviet Union, and no longer even pretended to be a free-market democracy.

Music and Political Ideology

Reflecting the Polish communist party’s consolidation of power and dissemination of the alien communist ideology, the film depicts the ensemble being directed to incorporate the praise of communist leaders and achievements of the party into their performances.

From 1949 until the mid 1950s Polish authorities even banned the broadcast of non-Polish or non-Soviet music. Instead, the approved music genre, so memorably presented in the film, was traditional or folk music infused with communist lyrics and propaganda. Not surprisingly, this gave rise to a musical counterculture. It revolved around Jazz, one of the music genres banned from the radio in 1949. Even public performances of jazz music were prohibited, as the authorities perceived it to symbolise western lifestyle.

During the Stalinist era of the early 1950s, thousands of Poles became political prisoners, some were sent to Siberian Gulags, while others were exiled. As the UB (the Polish Secret Service) numbers grew to one for every 800 citizens, and as citizens were recruited and encouraged to report on colleagues or neighbours, a climate of fear and suspicion descended on the country. The film demonstrates how many Poles saw informing on colleagues as a prerequisite to success.

Leaving Poland

Zola and Wiktor in the West

Understandably, many Polish citizens found life in communist Poland intolerable and left the country legally or illegally, as the both of the film’s main characters do.

Fearing a brain-drain due to the large number of Poles crossing the border illegally, or not returning, the authorities strengthened border security. Leaving the country without permission came to be viewed as tantamount to betraying Poland. Those in the public eye, who by leaving illegally also embarrassed the country, were dealt with very harshly, making the decision to leave virtually irreversible.

In East Berlin it was at first possible to ‘defect’ to the west by simply walking from the Russian sector to one of the Allied sectors of the city. This loophole for Eastern Europeans wishing to move to the west was closed following the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961.

Of course, Polish and other Eastern European artists on tour Outside of the Soviet block were known to defect or make contact with those who had earlier defected – something also integral to the film’s story.

Some two million Poles emigrated between 1946 and 1982. Emigration restrictions effectively confined legal departure from Poland to cases of family reunion and those asserting membership of ethnic groups seeking return to their homelands. In practice this caused many Poles to ‘discover’ previously unknown ethnic roots, seek to ‘marry’ a foreigner, or look for a ‘relative’ overseas.

However, to suggest that if given the opportunity, all Poles would have moved to the west, would be to restate western Cold War propaganda. It would also ignore the many reasons why those who left or visited the west found the west not to be the Nirvana they expected. Many former residents of communist Poland attest, that while living standards tend to be measured predominantly in terms of wealth, possessions and political freedoms, Poland offered a preferable quality of life through its focus on culture and life beyond work. In this respect the film resists making the cliched distinctions between the Cold War’s east and west, focusing instead on the non-commercial elements of life that matter most.

Corruption

Another aspect of Polish society, as it existed in the 50s and 60s and is explored in the film, is that of corruption, particularly in the form of endemic bribery. This ranged from turning a blind eye in exchange for a packet of cigarettes, through to almost unthinkable major life decisions. There is a discernible despair in the film’s presentation of what appears to be the nation’s loss of moral compass. In depicting far more than routine petty bribes, this film succeeds, as none other that I can recall, in confronting the viewer with the natural extension of the underlying amorality.

Jazz and the Revival of Polish Culture

The Jazz music that was banned in 1949 and features so memorably in this film, continued to be played in underground clubs, hidden from the prying eyes of the state. Following Stalin’s death in 1953, a more liberal faction of the party leader assumed power, relaxing the party’s authoritarian grip on Polish society. Laws restricting the types of music that could be broadcast and performed were repealed, allowing Polish jazz and early rock and roll to be played openly.

Dave Brubeck’s 1958 Tour

The Dave Brubeck Quartet played in Poland in 1958, becoming ‘the first American jazz musician to perform behind the iron curtain’. Brubeck is reported to have told his Polish audience that ‘No dictatorship can tolerate jazz…It is the first sign of a return to freedom’. Some commentators suggest that his prediction proved to be accurate as by the 1960’s Polish Jazz became a particularly significant element of the nation’s cultural revival.

While the post Stalinist years heralded the revival of Polish culture, including music, literature and cinema, the reforms did not extend to political freedoms. The liberalisation of the mid 1950s proved to be short-lived and did not lead to a democratisation of the Polish state. Instead it proved to be little more than a part of a repeating cycle of reform and repression – the latter often due to fear of Soviet intervention. Consequently early 1960s hopes for reform were also dampened by the middle of the decade, the period of the film’s final scenes.

Political and Personal Cold Wars

Zola and Wiktor

While the geopolitical Cold War setting is a key aspect of this film, I struggle to agree with the suggestion made by some commentators, that the film’s Cold War title also relates to the passionate, fiery and on and off relationship between Zula and Wiktor. I simply fail to see the depicted relationship as one of simmering or covert hostility. Instead, on the relevance of the Cold War setting, I suggest that the relationship between Zula and Wiktor would have been little different in the absence of the Cold War. On this basis, perhaps the story may just as satisfactorily be regarded as a Shakespearean tragedy or as a story of a relationship in which both parties feel they can’t live without the other while ultimately conceding that they also cannot live with them.

While the intensity of the main characters’ love and attraction created an addiction that was nigh impossible to break, and while the obstacles to their attainment of ongoing romantic happiness could be attributed to the Cold War, it is probably fairer to say that it was not the Cold War that created the hurdles and it was not the Cold War that made them insurmountable.

Finally, I must mention the film’s soundtrack of simply glorious music and dance. The folk, jazz and rock songs and visually stunning dances are simply mesmerising.

This is a film to savour and long remember.

(Visited 45 times, 1 visits today)