Folau: Courage of Convictions?

As almost everyone else seems to have an opinion about Israel Falau, I’d like to offer my perspective.

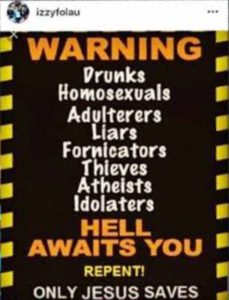

But first, a brief explanation for those who don’t live in Australia or follow Australian news. Israel Folau is an outstanding Australian International Rugby player. He is also an outspoken and committed fundamentalist evangelical Christian. He was raised a Mormon but is now associated with the Assemblies of God. He is about to lose his multi-million-dollar playing contracts with Australian Rugby and NSW Rugby Union because of his social media condemnation of amongst others, homosexuals, and his warning that unless they repent, hell awaits them.

His contracts, individual and collective, are said to require him to act and make statements consistent with Rugby Union’s promotion of inclusivity and respectful acceptance of diversity, including that of sexual orientation. His religious beliefs have led him to speak out against homosexuality in the past. His most recent outbursts on social media are alleged to constitute major code violations.

Radio host, Alan Jones

Having consulted Alan Jones, the (regretably) influential Australian radio’s populist, right wing talk-host, Folau has foreshadowed defending his remarks. He hopes to save his playing career by arguing that he was not under a personal contractual obligation to abstain from expressing his anti ‘homosexual’ views on social media, and that his sacking would amount to an infringement of his freedom of speech and freedom of religion.

As to freedom of speech, it will surprise non-Australians and many, if not most, Australians, that there is no legally enforceable freedom of speech in Australia.

The closest that Australia comes to having such a right is our High Court’s recognition of a freedom of political speech, implied by our constitution’s provisions regarding Representative Democracy. In the last few days the High Court has ruled that the implied right of political speech does not extend to demonstrating and ‘counselling’ against abortion in the vicinity of abortion clinics. Consequently I doubt very much that Folau’s condemnation of various groups including homosexuals would be deemed to be political speech.

Ultimately, The scope of freedom of speech in Australia is determined by asking whether particular speech is prohibited by law. If vilification, discrimination and similar legal prohibitions restrict Folau’s views, then his comments fall outside of the bounds of free speech as determined by our elected parliamentary law makers. Consequently, the religious basis for Folau’s remarks is only relevant if his religiously based statements are specifically exempt from the scope of such laws.

Australia’s constitution contains a provision that prevents Federal parliament from being able to enact laws to restrict the free exercise of religion. This provision has been interpreted to only apply to federal laws enacted with the purpose of restricting the free exercise of religion.

In practice while Australians are free to believe whatever they want to believe, our freedom to exercise or implement our beliefs is not limitless and is subject to compliance with other laws. Consequently while Folau is entitled to hold religious beliefs about homosexuality, if he expresses his views in a manner prohibited by law, the fact that his motivation was religious will not help him.

Folau acknowledges God on the field

It would appear that Folau feels that his religious beliefs require him to speak out, expressing views that are contrary to contemporary social values, laws and institutions. A comparison of how Folau and Australian society regard the targets of his social media messages clearly highlights the nature and extent of difference.

‘Drunkards’ – Australians (including Christian Australians) prefer to see people with alcohol abuse issues as people in need of assistance and treatment, rather than as people destined to go to hell unless they repent and are saved by Jesus.

‘Homosexuals’ – Australians have legalised homosexuality and more recently same sex marriage. The vast majority of us, religious and non-religious, reject the view that homosexuals must repent and repress or treat their homosexuality. We do so because homosexuality is no longer perceived (by almost all of us) to be either a choice or a perversion. To remove remaining prejudices and discrimination, many institutions are currently engaged in programs promoting the acceptance and inclusion of same sex people. This is the case in many sporting competitions, including Australian Rugby.

‘Fornicators’ – Fornication is a term that describes consensual sex between two unmarried adults. As premarital sex is no longer socially unacceptable, living together without marrying is increasingly common, and only a small fraction of couples marry without having had premarital sex.

‘Adulterers’ – Adultery, or sex involving a married person and a third party, married or unmarried, is no longer a grounds for divorce, nor a ground for any kind of secular sanction. However, adultery continues to be recognised as a major cause of marital breakdown. Dissolution of marriage is declared on a fault free basis and does not carry social, or increasingly even religious, stigma. While widely condemned, adultery is tackled by civil authorities and mainstream churches through education and counselling rather than through calls to repent or be condemned to hell.

‘Liars and Thieves’ – Similarly liars and thieves are perceived negatively and in some circumstances as criminals in need of rehabilitation or punishment, but not in terms of being in need of being saved by Jesus.

‘Atheists’ – Those who don’t identify with any religion now constitute the second largest ‘religious’ group in our society. Folau’s implicit suggestion that atheists should heed his warning that hell awaits them and that they need to repent as only Jesus saves, is problematic. Basically his message is that those who by definition don’t believe in God or hell should repent and be saved the Jesus they don’t believe in, in order to avoid going to hell, a place they don’t accept as real. But apparently logic is not permitted to get in the way of a stirring and supposedly serious message.

‘Idolaters’ – A term that describes those who worship something or somebody as if they were God. Arguably, anyone who pursues a passion and does not worship Folau’s God would fall into this category. Those of us with decorative statutes of Buddha in our gardens should take note.

Surely Folau realizes that his religious views are not shared or appreciated by the majority of the population, both religious and non religious. If they were, it could be suggested, Folau would not feel as compelled to speak out.

The married Christian couple

Folau must be aware of the chasm between his religious views and public campaigns to promote diversity and the acceptance and integration of what he describes as ‘homosexuality’. As a professional Rugby player Folau is aware of how the authorities governing his sport are actively involved in promoting such messages and expect players to play their part or at least not act in a contrary manner.

Whether he expressly agreed to be bound by a Code of Conduct provision explicitly promoting values contrary to his religious beliefs and requiring him from using social media in a contrary manner is being contested. What cannot be contested is that he knew that in order to play professional Rugby in Australia he was expected to agree (even if without specific mention of the use of social media) to act consistently with the immunity programs advocated by the game’s administrators. Consequently, he should not be surprised that he is accused of a code violation that entitles his employers to terminate his contracts.

I invite Falau to imagine me taking up a position of employment with his church and signing a contract to uphold standards of behaviour consistent with those of his religious organisation. If subsequently I posted online a photograph of me on a float at the Sydney Gay Mardi Gras, would he not feel betrayed and justified in terminating my contract? Would he not consider my religiously based pro gay equality views to be irrelevant to my breach of the work agreement? Would he also not consider any arguments suggesting that I did not agree to any clauses specifically relating to social media as mere hair-splitting that did not alter the fact that I had breached an agreement to abide by the Church’s standards?

The Folau controversy also highlights a rarely discussed implication of freedom to exercise religion or express religious views. The expression of religious beliefs may not, as is commonly presumed, be an expression of tolerance and love, but rather one of condemnation designed to make those deemed sinners recognise that they are doomed unless they repent. Such condemnation, society recognises, is particularly troubling for same sex people who find that they are unable to alter their sexual orientation.

The reality is that the expression of religious beliefs may vilify those engaged in behaviour acceptable to society but not condoned by certain religions, or by those holding certain interpretations of religious teachings.

It is also important to recognise that the limits of religious freedom are not determined by the plausibility, logic or consistency of beliefs. As former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke pointed out in response to public ridicule of indigenous spiritual beliefs, such beliefs are no more ridiculous than the beliefs of Christians when viewed from the perspective of a non-Christian.

What our law recognises as religion is not determined by its credibility as perceived by outsiders. Consequently, it is not for us to question beliefs by for example pointing out that a condemnation of a behaviour because it is prohibited in the Bible is not compelling unless other biblical prohibitions are also taken seriously.

Margaret Court

I must admit that I have been guilty of such criticism when, for example, reacting to Margaret Court’s condemnation of same sex relationships, while she ignores clear New Testament directives that a woman is not to speak in church – let alone set up her own church and appoint herself the spiritual leader of a church, as she has done. On reflection I should not have done so, as it is not for me to determine what is or is not a genuine religious belief. For this reason I argue that Christians and others have no right to question Falau’s religious beliefs, although they do have a right to criticise him for how the exercise of his beliefs affects others.

Ultimately in my view it is unlikely to be found that the response of Folau’s Rugby employers to his condemnation of homosexuals amounted to a breach of his religious freedom or freedom of speech. The Code which he is guilty of violating is also unlikely to be found to be discriminatory in that what it asks of players is not a breach of their right to believe. The Code may be more accurately described as prescribing a code of conduct with the intention of preserving respect between different sectors of society, including groups holding differing views and religious beliefs.

But, what if the code was found to discriminate against those who feel obliged by their religion to condemn others? While I should sympathise with Falau, I would struggle to do so given the circumstances. In accepting the conditions of his employement he agreed not to do what he claims his religious beliefs require him to do. He did not have to enter into an agreement that compromised his religious beliefs – even if such a stand would cost him a lucrative contract

Often there is a price to be paid for choosing to act ethically, in accord with conscience or our religious beliefs. We have heard of Jewish AFL footballers whose careers were seriously impeded because their religious beliefs prevented them from playing between sunset Friday and sunset Saturday. being able to enjoy what’s incompatible with religious freedom. Folau could have taken such a stance, but instead he wants to maintain his religious beliefs while gaining the benefits of involvement with a sport committed to promoting values incompatible with his beliefs.

Rights, including our right to practice religious beliefs cannot be considered in isolation, and must be weighed against competing rights of other members of our community. For this reason, at times the exercise of religion may need to be limited. To accept the cost is the price believers pay for having the courage of their convictions.